Athletes Struggle Too: The Relationship Between Sports and Mental Health

February 8, 2023

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University estimate that 21% of student athletes are diagnosed with depression. But many more are never diagnosed, and the actual number of student athletes who struggle with mental health is likely much higher.

The situation is no different at RAHS. Although the school doesn’t often recognize or support athletes struggling with their mental health, it is an issue that touches nearly every student athlete in RAHS programs.

Because mental health is a sensitive issue that can be difficult to discuss, the names of the people interviewed for this article have been changed.

Elis is a sophomore at RAHS. She plays hockey and lacrosse. Lacrosse, she plays for herself, while hockey, she plays “for everyone else.” She said she has a love-hate relationship with hockey, because although she has fun playing, everyone’s expectations of her make it difficult to truly enjoy her time on the ice.

Elis commented that one of the biggest reasons that she struggled with hockey was her mental health. She was diagnosed with depression about a year ago, but she had always shown signs of mental illness.

Elis said that depression made her hate hockey. “It makes me not want to play. And it makes me hate everybody involved in hockey, which is really unfair.”

She said that her depression affords her an excuse to act out and give up on herself. She knows that she should work hard at her sports if she wants to get better, but her depression gives her a convenient way out, a way out that she often wishes she didn’t have the option to take.

Over time she has attached her “entire value” to the sport and, since most of her social circle is intertwined with the hockey community, she feels like her peers “won’t value [her] if [she’s] not good at hockey.”.

Although she knows this is not true, she underscored how hard it can be to sort the lies from the truth when your brain constantly tries to deceive you.

In contrast to her relationship with hockey, Elis plays lacrosse for fun. She noted the toll that playing a sport for everyone else takes on her, and said that the difference between playing for herself and for other people is “almost like night and day.”

She still deals with the same problems when she plays lacrosse, but said “it’s a lot easier to deal with them when I’m playing lacrosse, because I look at the two so differently.”

Elis noticed that her teammates struggle with similar things: they associate their personal value with their performance as an athlete. One of Elis’s closest friends on the team, who she described as “extraordinary at hockey,” described uncertainty about her future away from the sport. She asked, ‘What am I if not a hockey player?”

Olivia, a Junior who plays tennis and basketball, felt similar pressures. She elaborated more on the idea that yes, sports can negatively impact self esteem, but this pattern becomes a cycle when negative self esteem makes an athlete “play scared.” This cycle makes an athlete feel worse and worse about themselves and in turn, they perform worse and worse at their sport.

Olivia also mentioned that the season has a huge effect on both mental health and mindset towards sports. She has Seasonal Affective Disorder, but seasonal issues impact most winter athletes.

In the winter, many athletes start their day either at school or in the gym before the sun is up, and most do not get home from practice until long after the sun has set. Olivia said that “when it’s winter and it’s dark out all the time, everything can kind of start to weigh down on you all at the same time.”

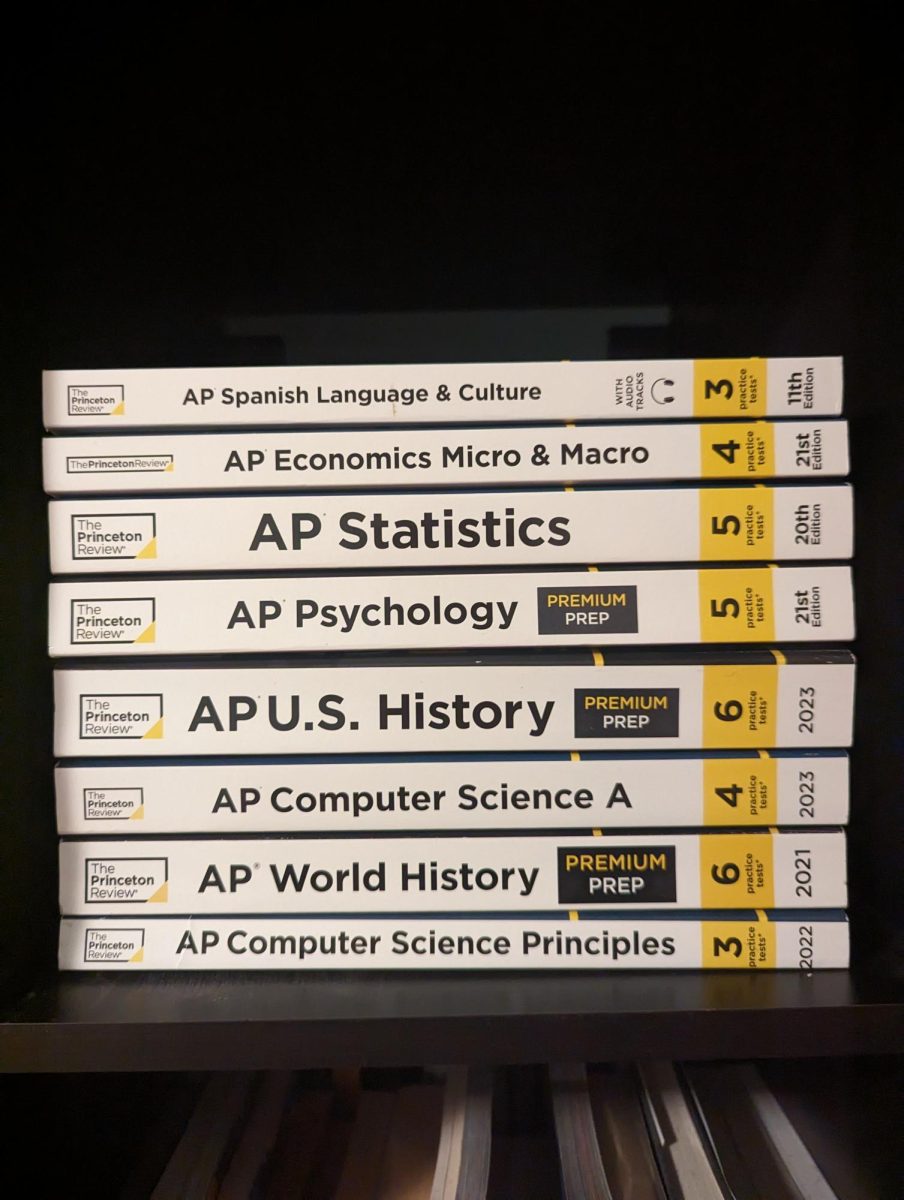

This is a lot for anyone to deal with, but when you add in pressure to perform well both athletically and academically, it can amount to a recipe for burnout or even more serious mental health issues.

It can be easy to overlook the struggles of successful athletes, since they seem to have what so many others want. This mindset is very damaging for people like Olivia, who performs at a very high level in both of her sports. She commented that imposter syndrome and performance anxiety are issues that she deals with regularly, and when you play on a team, there’s always the idea that you could be letting someone down.

Olivia turns to both her teammates and her friends outside of her sport for support when she’s struggling. She noted the importance of balance, because it can be really helpful to talk to both people who know that you’re going through and people who are removed from the situation.

She added that it can be difficult to reach out to teammates, because “if somebody else is doing well and you’re not, it can make you feel wrong for wanting things to be different when other people are having success.”

Having struggled with depression, Olivia believes that mental health in sports can be improved by acknowledging the failures of the systems that exist and working not only to fix these systems, but also to create new ones that prioritize mental health.

Despite the prevalence of mental illness in high school sports, mental health is rarely a focus for coaches and people in control of athletes. Olivia acknowledged that coaches try to relate to their players, but the environment has changed so much since they were athletes themselves that they often cannot fully understand what’s going on.

Lucas, a senior who plays hockey and football, disagrees with this idea. He believes that it is not a coach’s job to look after athletes’ mental health. He said, “coaches are there to take care of your performance in your sport. It’s your job to take care of your mental health.”

He commented that coaches not being involved doesn’t have to mean athletes are entirely on their own. Lucas thinks athletes should reach out to each other when they are struggling. He noted the added benefit of this approach: team bonding. “Being there for your teammates is a great way to build a strong team.”

Lucas viewed the relationship between sports and mental health as less widespread and prevalent than Olivia and Elis did. He acknowledged the link between pressure to perform and declining mental health, but he also values this pressure as a motivator. He said it drives him to work hard and prioritize his success in both of his sports.

If you or someone you love is struggling with mental health, text or call 988 (National Suicide Hotline), or text ‘home’ to 74171 (MN Crisis Line).