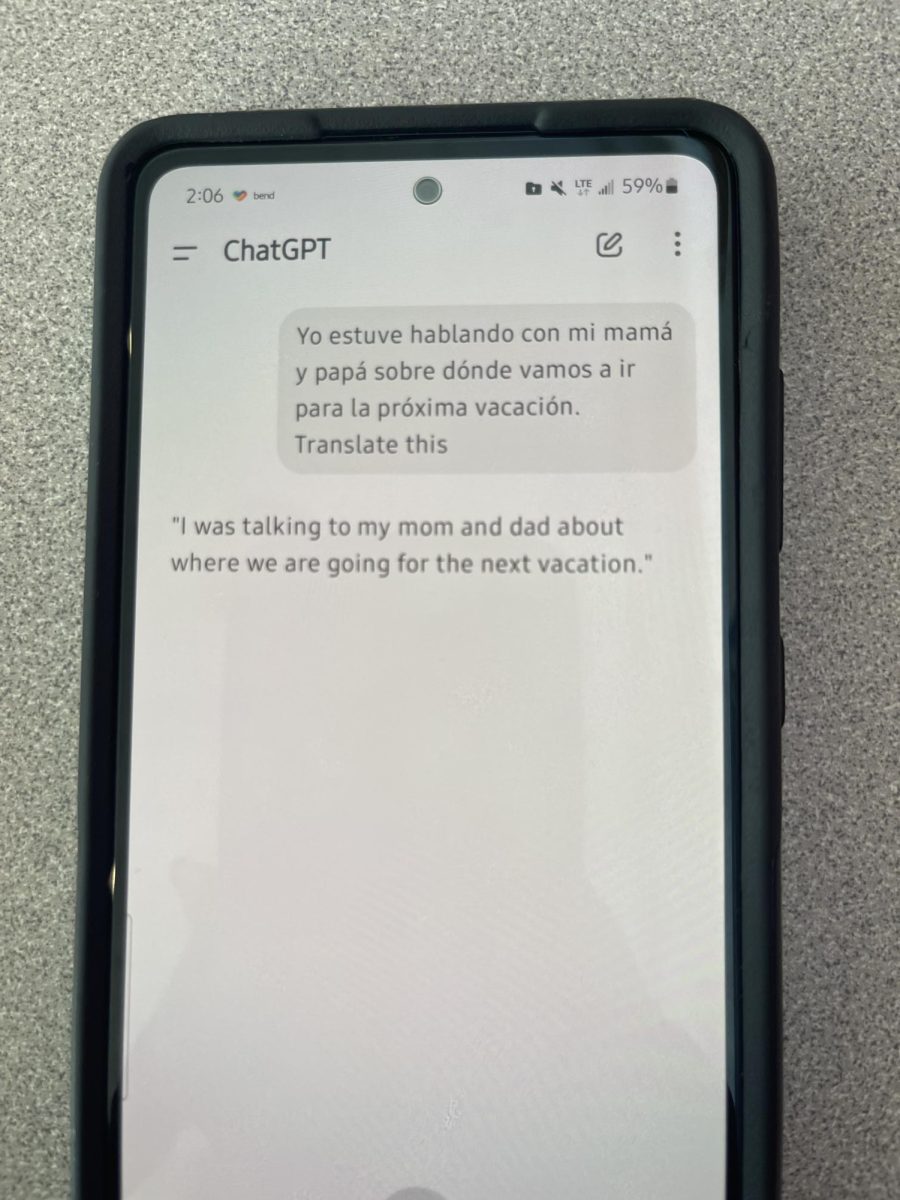

Currently, there is no policy in the RAHS student or staff handbook that officially mentions the words “artificial intelligence” under the plagiarism category. As AI tools like ChatGPT, Grammarly, and AI image generators become more common in education, the lack of clear guidance leaves students and staff to navigate the uncertainties. Should AI be embraced as a learning aid, or does it cross ethical boundaries?

RAHS Principal Dr. Jen Wilson also has mixed feelings about AI. She said, “I think AI can be a useful tool…I also understand that it can be used in not good ways, like when students are plagiarizing something. So it’s both, I can see it as a good and bad.”

Without an official stance, RAHS students and staff are left to interpret AI’s role on their own, leading to inconsistent expectations and confusion. However, Dr. Wilson shared that the discussion around AI is constantly developing into a clearer stance. For now she pointed out what is included in the student and staff handbook under plagiarism can be used as a guide.

She said, “We have talked about it a ton, especially in regards to the student handbook but it all falls under plagiarism…if a student uses [AI] and tries to submit it as their own work, teachers have done a decent job at navigating if it’s come from a student or AI, and if [the student’s work] did come from AI, they would follow our plagiarism policy.”

Dr. Wilson said she believes that plagiarism when using AI is straightforward—it occurs when students copy AI-generated text word-for-word in their assignments.

However, Jamie Crandall, RAHS’s technology integrationist, sees a more complex issue. Crandall said, “With this training and with what knowing AI can do, there’s still the big question of what is plagiarism. Where is the line drawn between plagiarism and using AI? I’d really like students to have clear guidance from teachers like ‘You can use ChatGPT for this part of the assignment, but not for this part’.”

Although there is no official policy on AI, Crandall pointed out that on February 10, 2025, the school board held a meeting where they drafted an update to the acceptable use policy, explicitly including the term “artificial intelligence.” The draft can be found under Policy 400P, titled “Acceptable Use.” District Policies – Roseville Area Schools 623

Even though this is written documentation, it is only a draft, and it is vague on when AI can be used. Crandall highlights the difficulty with restricting the use of AI entirely, as it offers valuable capabilities that are a quick and easy source for students to turn to. For example, she explained that students can input assignment instructions into an AI chat and ask it to reword or clarify them, making it easier to understand what is being asked.

Crandall has been pivotal in educating teachers about AI and guiding them through its complexities. She shared a useful acronym with me that she found—one she also introduced to teachers—that I believe would benefit every student as well:

Converse: Engage with ChatGPT in a dialogue. Chat! Remember, it’s not a simple search engine.

Hypothesize: Predict possible responses to your questions. This will help you identify errors.

Adapt: If the first response isn’t what you need, reframe your question or dive deeper into the topic.

Think: Reflect on the responses. Do they make sense? Are they accurate? Are they potentially biased?

Gather: Use ChatGPT as a tool to gather information, but cross-verify with other sources.

Probe: Ask follow-up questions. Seek depth in understanding. Don’t settle for the first answer.

Train: Continually refine your interaction with ChatGPT. Learning to use it effectively is an ongoing process.

Source: Help Students Think More Deeply With ChatGPT | ISTE

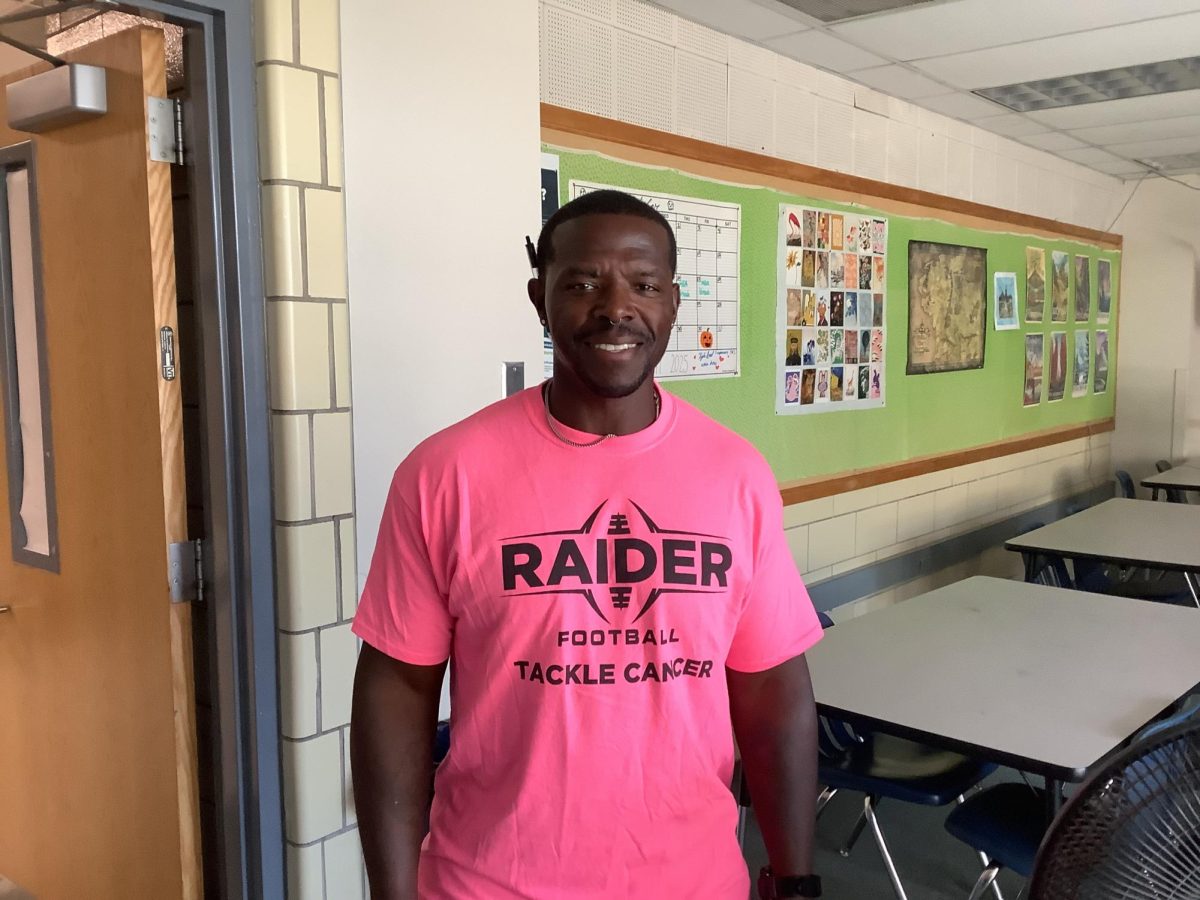

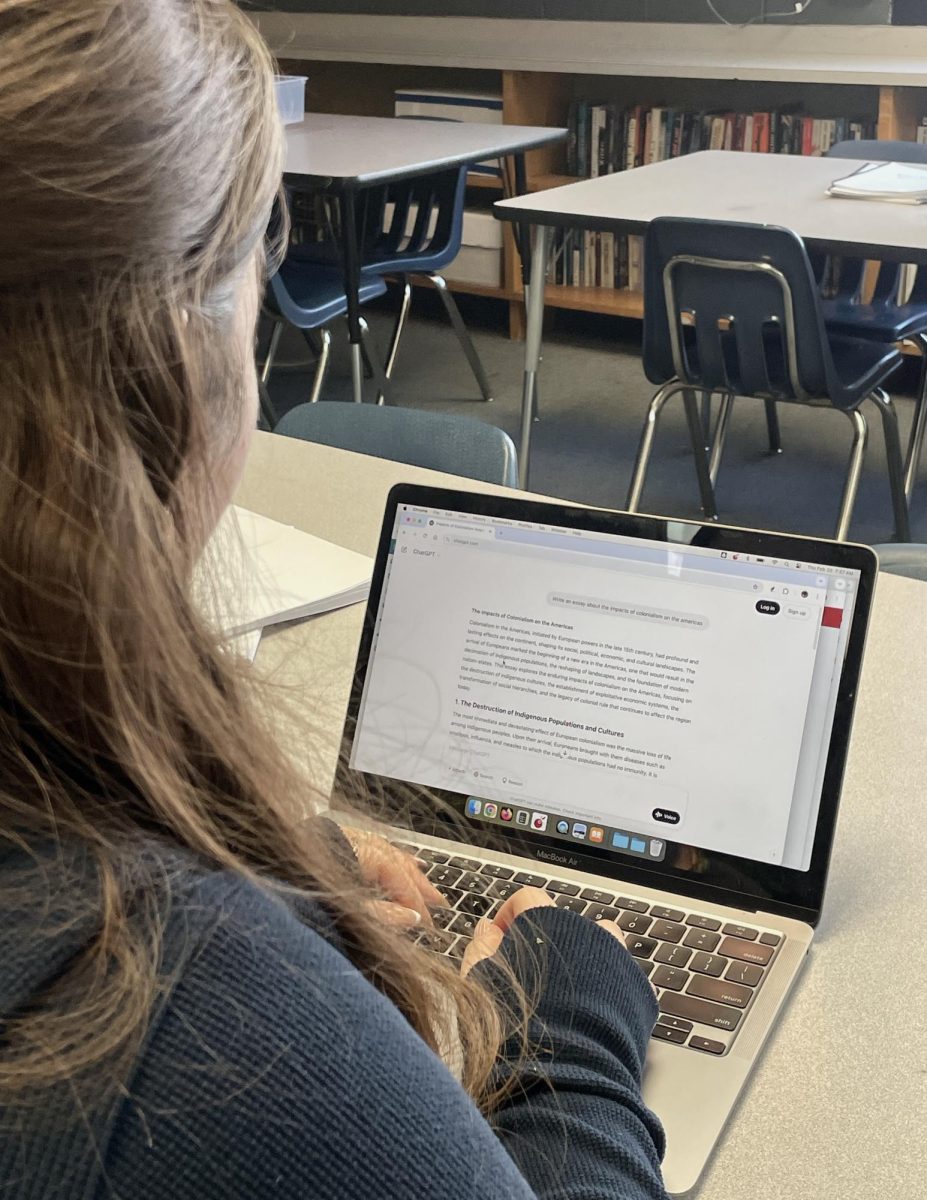

Shifting perspectives, I interviewed English teacher and chair of the English department, Pierre MacGillis, to gain insight into how AI is impacting the classroom from a language and literacy standpoint.

MacGillis shared, “I have real concerns about detrimental effects on students’ ability to think clearly, trust their own thoughts, and trust their own writing process. I understand that in some contexts, AI is valuable and saves time, but from the particular perspective of an English teacher, there are so many distractions that aren’t the students’ faults, but that already make it hard to think and focus on great ideas that aren’t always easy to wrestle with or understand”.

MacGillis also shared insights from a broader English department perspective as well, highlighting how the faculty is approaching this evolving technology, “There’s not just one position for the department, but the default position is that any AI program that generates language is not acceptable for use. There’s a small committee in our department that has been working on creating a kind of a template that would be consistent, including the kind of values we can all agree on…they are looking at different perspectives and trying to generate a clear document that outlines and expresses the English department’s clear position”.

Finally, he said, “I would just want clarity and a clear position [for an AI-specific policy]. It would be nice to give students some guidance on what might be ethical in this case…I think the English department is in the process of doing this and determining what is considered wrong or unethical while using AI”.

While there is no clear policy on AI at RAHS, the conversation around its use is rapidly evolving. As many educators, including Dr. Wilson, Ms. Crandall, and Mr. MacGillis, work to navigate its complexities, it’s clear that AI is reshaping the world of education. Although there is no definitive written answer yet, RAHS must continue to adapt to the changing nature of AI, ensuring both students and staff have the guidance they need to use these tools ethically and effectively.